Identity

Usefulness and services of the tree :

Features and characters of the individual

These are four of the last elms in the region. They are the survivors of the works on Boulevard du Botanique and Petite Ceinture, and they show resistance to the Dutch elm disease that threatens this species with extinction. They are the trees of American Indians.

A tough old pair

Two survivors

This pair of field elms are among the last four of their kind in Brussels. It is a wonder that they are still standing at the bottom of the Boulevard du Jardin Botanique, surrounded by eight lanes of traffic.

These trees have endured many trials. They have experienced several phases of redevelopment of the boulevard. When the Rogier tunnel was being excavated, for example, their roots were severed. They spent several months exposed to the open air, and thus to all kinds of pathogens (diseases).

These two individuals are still standing, while the entire population of elms in Brussels and Europe has been decimated by Dutch elm disease. In fact, this species has an impressive history in the major cities. It has adorned and shaded long avenues. A stately presence with its straight trunk, a crown that can reach up to 30 metres in height and, above all, a broadly fanning top that casts a gentle shadow. Unfortunately, in the mid-20th century this species was besieged by disease. The great elms practically vanished in the 1980s.

Dutch elm disease is caused by a fungus that is spread by an insect, the bark beetle. It is thought to have arrived in Europe in 1919, in the hold of a boat with a cargo of timber from the USA. The little beetle gnaws at the wood just beneath the bark. It chooses its victims well: large trees with trunks over 40 cm around. The Dutch elm disease takes care of the rest. It starts by preventing the tree from growing larger and ultimately kills it. This is why large specimens have become rare in our regions.

These two field elms have thus made history on the Boulevard du Jardin Botanique. One of them is the largest of its kind. Ordinarily it should have attracted bark beetles long ago. In recognition of this extraordinary resistance to the natural and man-made hazards, they were included in the inventory of notable trees in 2012 and on the preservation list in 2014. The hope is that this will help them to remain standing for two or three more centuries: field elms can live up to 400 or 500 years.

United we stand

How have these two forces of nature managed to hold their own in such a hostile environment? Their leaves are exposed to massive amounts of particles. Their entire surface receives the shocks of the traffic whizzing by them, not to mention being buffeted by the sound waves of the car horns and sirens that constantly pierce the air. Their roots endure the sub-bass vibrations of heavy trucks and non-stop traffic over concrete.

Could it be because they are a couple that these two trees have been able to survive against all odds? In principle, the roots of elms tend to prefer rather cool, clay-rich, fertile soils, which is certainly not what is found beneath the sidewalk here. Today, we know that trees can communicate through their roots and live in symbiosis with mushroom mycelium. In the forest subsoil, trees can thus help each other across very long distances. They can exchange mineral salts. But how could this work in a soil as poor as whatever there is below the sidewalks and paving stones of the boulevard? Roadside trees are often highly fragile. But these elms stand defiant.

Survival strategy

These two trees appear all the more static as the traffic swirls around them. And yet, they are not quite as immobile as they seem.

Scientists have discovered that elms are able to emit molecules that attract the predator of their insect foe. This defence must have always been latently present in the DNA of elms, but is only expressed in rare individuals. Could our two elms have used this potential throughout the 20th century to slowly but surely defend themselves against attack? It remains an open question. It is interesting to consider, however, as it confronts us with a completely different scale of time: that of the tree, which seems immobile, practically inert, in our eyes.

This question casts new light on our tendency to take direct action: in attempting to eradicate the disease, we humans have felled entire avenues full of elms. Among them, perhaps healthy individuals who may have also possessed this capacity for resistance. We might do well to learn from their example and allow nature the time to show us what it can do.

In this regard, the elm has another strategy that has allowed it to reproduce via the air for more than 100 million years. It has a particularly mobile mode of reproduction. If you walk along the boulevard in the springtime, you will notice a scattering of airborne seeds drifting across it. These are called samarae. These small round seeds are encased in the centre of two flat, semi-circular, paper-thin lobes that act as a large sail. The ride the wind to travel hundreds of metres away. Unfortunately, these seeds are unlikely to germinate naturally in this largely paved over district. If they happen to land on the other side of the inner ring road, on the lawn in the Botanical Garden, they risk falling prey to the lawnmower. The best would be for them to reach a wooded area.

Which one doesn't belong?

In this line of trees, there are two elms that are thus hiding among the plane trees. How to recognise them, if you do not know exactly where they are located?

The bark of these two field elms on the boulevard has become so darkened that it is hard to pass them without noticing the difference. This brownish-black colour (in adulthood) is not the result of the accumulated pollution of the traffic, however. It is the natural colour. The bark is deeply furrowed. It is so dark that in Greek mythology, the elm was considered the guardian tree of the gateway to the underworld. Here, it has also inspired a graffiti artist to splash a cross of red paint on one of the two trunks.

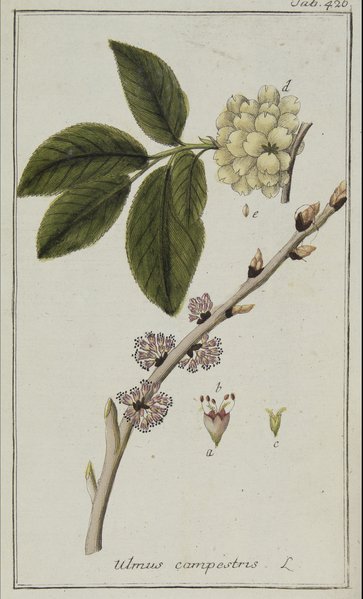

Furthermore, the elms are recognisable especially for their leaves: more or less oval in shape, with serrated edges, slightly rough to the touch. But particularly, as they are asymmetrical, with one half beginning higher up on the central vein of the leaf than the other. This is the one feature that distinguishes these trees from all others with oval leaves: hornbeam, beech, hazel, etc. A slight asymmetry that is part of its charm.

If you have the chance to gather the fallen twigs at the foot of the tree, or find yourself within reach of suckers (young branches growing from the trunk), you can observe the buds. They are small and pointed, with velvety scales. They alternate on the stem and grow obliquely above the leaf scar. They also appear slightly cockeyed, or ‘schieve’ in Brussels argot. Perhaps that is why these two individuals seem more at home in Brussels than in the fields from which they take their name 😉.

This portrait is enriched with an illustration from the Belgian Federal State Collection on permanent loan to the Meise Botanical Garden. See attached. Thanks to the library (heritage collection) for this contribution. https://www.plantentuinmeise.be/en/home/